"While some authors suggest that the complexity approach may be better for facilitating widespread phonological change (i.e., Gierut 2007), others do not support this position (Rvachew & Nowak, 2001; Rvachew and Bernhardt, 2010). To date, no single approach has been reported to be the most ideal. Adequate comparative research simply has not been done. Additionally, what may be best for one child at a particular time may not be the best for another."

McLeod and Baker (2017, p.350)

Target Selection

-

1. Developmental - Conventional minimal pairs

Suitable children:

- Children with SSD

- Children with low resilience or who become frustrated easily

(McLeod and Baker 2017)

Selecting targets:

- Sounds or processes that affect the child's intelligibility

- Early developing sounds

- Stimulable sounds that are included in the child's phonetic inventory

- Sounds that the child has some productive phonological knowledge (PPK) of

(Dyson and Robinson, 1987, in McLeod and Baker 2017)

NOTE: "If rapid completion of treatment steps in a short number of sessions or learning of the treatment target primarily is the goal of treatment, then treatment of most-knowledge/early-acquired targets through the sentence level may be optimal. On the other hand, if system-wide phonological change is the goal of treatment, then treatment of least-knowledge/late-acquired targets through a required set of treatment steps may be optimal." (Storkel, 2018, p.3)

-

2. Systemic - Multiple oppositions

Suitable children:

- Children with system-wide phoneme collapse (i.e., the use of one sound in the place of many others (e.g. [t] in the place of /k, ʃ, s, p/).

(McLeod and Baker 2017)

Selecting targets:

Within the child's phoneme collapse a maximum of 4 sounds are chosen for intervention based on a distance metric:

- Maximal classification: i.e., different manner classes, places of production and voicing (e.g. /ʃ/ vs /m/)

- Maximal distinction: i.e., sounds that are maximally distinct from the child’s error in terms of place, voice, manner and linguistic unit (e.g. singleton vs cluster)

(Williams 2005b)

Materials:

-

3. Complexity - Maximal oppositions, empty set, 2/3-element clusters

Suitable children:

- Children with a SSD

- Children with a restricted phonetic inventory

- Children with no co-occurring difficulties (i.e., intelligence, attention and listening, oro-motor difficulties, hearing difficulties) (Bernhardt, Stemberger and Major 2006, Bleile 1996, Gierut 1999)

- Children with typical expressive and receptive language skills (Gierut et al. 1996, Gierut 1998a, Gierut and Champion 2001)

Selecting complex targets:

(1) Non-stimulable sounds

- Stimulability is the elicitation of a single phoneme in at least 2 positions (i.e., CV, VC)

- Non-stimulable sounds are less likely to change without treatment (Miccio et al. 1999)

- Powell and Miccio (1996) Stimulability test (via speech-language-therapy.com)

- Non-stimulable: if the child imitates the target 0-2 times.

- Stimulable: correct imitation of a target 3 or more times (Miccio 2002).

(2) Sounds with least productive phonological knowledge (PPK)

- PPK is the accuracy of phoneme realisations in a child's speech. This can range from 0% accuracy (low PPK) to 100% accuracy (high PPK).

- Greater system-wide change may be produced by treating sounds with a low PPK

- For more information, please see: The complexity approach to phonological treatment: How to select treatment targets (Storkel 2018).

(3) More marked sounds

- Marked sounds are more linguistically complex (phonologically and phonetically) than unmarked sounds (Storkel 2018).

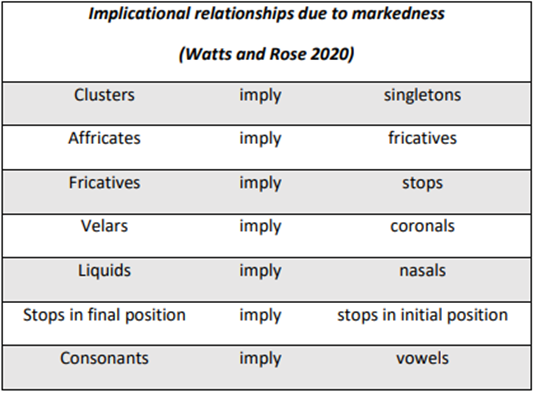

- The use of marked sounds in therapy (i.e., more complex sounds) is said to lead to greater system-wide change than the use of unmarked sounds (Gierut, Silverman and Neumann 1994, Dinnsen and Elbert 1984). See Figure 1 below for an overview of potential implicational relationships between targets selected and subsequent developments within the child's speech sound system due to markedness (Watts and Rose 2020).

Figure 1: Potential implicational relationships between targets selected and subsequent developments within the child's speech sound system due to markedness (Watts and Rose 2020)

2-element clusters:

- For 2-element clusters, Storkel (2018, p.5) suggests working on sounds with a sonority difference of 3 (i.e., fl, fr, thr, sl, shr) or 4 (i.e., bl br, dr, gl, gr, sw) in order to replicate the results of the research by Gierut and colleagues (See Table 1 below for more information). Storkel (2018) recommends that /sm/ and /sn/ are not targeted because they may behave like the adjuncts /sp, st, sk/ and produce mixed outcomes (Gierut 1999, Gierut and Champion 2001).

- This selection of 2-element clusters with smaller sonority differences between elements (more marked) may help drive more systemwide change than those with larger sonority difference between elements (less marked).

- Be mindful that the elements within clusters and the frequency of cluster-type also play an important role in acquisition (Watts and Rose 2020) and may also be used to support target selection.

- Note also that there is not a direct relationship between targeting more marked clusters and more widespread change to the child’s speech, and such relationships would be expected to change across languages (Watts and Rose 2020).

2-element Clusters Complexity from most to least complex (top to bottom) Clusters Sonority difference 3-element clusters skw, skr, spl, spr Voiceless fricative + nasal *sm *sn 2 Voiceless fricative + liquid fl fr thr sl shr 3 Voiced stop + liquid or Voiceless fricative + glide bl br dr gl gr sw 4 Voiceless stop + liquid pl pr tr kl kr 5 Voiceless stop + glide tw kw 6 Table 1: Complexity of clusters (Adapted from Bowen (http://www.speech-language-therapy.com 1998-2013), Gierut (1999), Gierut and Champion (2001), Morrisette et al. (2006) )

3-element clusters:

- The treatment of a 3-element cluster is recommended only if the child has the second and third elements of the cluster within their phonemic/phonetic inventories (Gierut and Champion 2001).

- If the child has the initial cluster element (i.e., /s/) to a higher degree of accuracy than the other elements of the 3-element cluster, then all 3-element clusters are not suitable for treatment.

- For more information please see: The complexity approach to phonological treatment: How to select treatment targets (Storkel 2018, p.11).

(4) Later developing sounds

- Earlier developing sounds are said to be acquired 1 year before the child's age (Smit et al. 1990).

- Later-developing sounds are considered to be acquired ≥1 year beyond the child's age (Smit et al. 1990).

- Targeting later-developed sounds in therapy is said to be more effective in bringing about system-wide change and generalisation than using earlier-developed sounds (Gierut et al. 1996, Gierut and Morrisette 2012). However Rvachew and Nowak (2001) and Dodd et al. (2008) contradict this finding.

Table 2: Early, middle and late developing sounds (Shriberg 1993) Early-8 m n j b w d p h Middle-8 t ŋ k g f v tʃ dʒ Late-8 ʃ ʒ l ɹ s z θ ð and clusters (see Table 1) NOTE: "If rapid completion of treatment steps in a short number of sessions or learning of the treatment target primarily is the goal of treatment, then treatment of most-knowledge/early-acquired targets through the sentence level may be optimal. On the other hand, if system-wide phonological change is the goal of treatment, then treatment of least-knowledge/late-acquired targets through a required set of treatment steps may be optimal." (Storkel, 2018, p.3)

Why use complex targets?

Using complex targets in therapy may prompt more rapid, system-wide change in a child's speech sound system than using less complex targets (Gierut 1991, Gierut 1990, Gierut 1998, Gierut and Champion 2001, Topbaş and Ünal 2010).

Treatment words

When using the complexity approaches, target any of the following word types and combinations depending on the child’s presentation to produce most rapid, widespread effects:

- High frequency and high density;

- Low frequency and high density;

- High frequency and mixed density;

- Low frequency and later acquired;

- Non-words.

Children who have difficulties with vocabulary acquisition will fare better with options using high frequency vocabulary (Storkel 2018).

Examples: Word types:

High frequency - a word which occurs a high number of times in a language (i.e., man, dog)

Low frequency - a word which does not occur frequently in a language (i.e., agitate, erupt)

High density - words with a high number of minimal or near minimal pairs (i.e., cat, pat)

Low density - words with a low number of minimal or near minimal pairs (i.e., igloo, letter)

For more information please see: Implementing evidence-based practice: Selecting treatment words to boost phonological learning (Storkel 2018)

Materials

Materials:

- Good practice guidelines for the analysis of child speech - Speech analysis checklist (P16 - 22)

- Phonological Assessment and Treatment Target (PATT) Selection tool (Barlow, Taps and Storkel 2010)