Page content

Student Engagement and Partnership

At Ulster University, student engagement is about more than just collecting feedback - it’s about building shared responsibility.

We see partnership as a way of working where students and staff collaborate to co-create learning, enhance teaching, and shape the university experience.

This approach reflects our principles of inclusive, active and collaborative learning and supports better working lives across our community.

“Student–staff partnership is not a project or product — it is a mindset, a culture, and a commitment to shared responsibility.”

(Peart, Rumbold & Fukar, 2023)

Why Partnership Matters

A growing body of research shows that student–staff partnerships:

- Enhance belonging, identity, and wellbeing, particularly for underrepresented students (Baxter, 2018)

- Motivate student engagement by enabling co-creation with whole cohorts, not just selected individuals (Bovill, 2017)

- Develop graduate-level skills such as communication, reflection, and leadership (Ansley & Hall, 2019)

- Shift traditional hierarchies by promoting shared ownership and inclusive curriculum design

- Are most effective when embedded institutionally and grounded in shared values (Healey et al., 2014; Healey & Healey, 2019)

Partnership at Ulster: Principles in Action

Ulster’s approach is grounded in our Learning and Teaching Principles - Inclusive, Active and Collaborative Learning, Continuous Enhancement, and Better Working Lives - and in our eight Learning and Teaching Qualities.

These values underpin how partnership is embedded into everyday teaching and institutional decision-making.

Learning and Teaching

Students work alongside staff to co-design assessments, shape module content, and contribute to the development of digital tools and resources.

These practices support Active and Collaborative Learning, promote Authenticity, and build meaningful Relationships. Through platforms like Explorance Blue, student feedback informs enhancement - aligned with our focus on Digital and Data, Continuous Enhancement, and Valuing Voices.

Curriculum and Quality

Student representation plays an important role in curriculum design and programme review processes, through Student Representatives sitting on Staff -Student Consultation Committees and in the Student Panel initiative.

Student contributions ensure our decisions are inclusive and evidence-informed - supporting Inclusivity, Research-Informed practice, and improved Outcomes and Experience. This shared responsibility contributes to Better Working Lives for both staff and students.

Representation and Voice

In partnership with UUSU, students influence decision-making through university committees, student panels, and local feedback loops. These structures encourage a culture of mutual respect and advocacy — reflecting our commitment to Wellbeing, Valuing Voices and Advocacy, and Authenticity.

Innovation and Inclusion

Ulster students co-lead enhancement projects focused on EDI, sustainability, assessment reform, and inclusive curriculum design.

These projects reflect our commitment to Inclusivity, Sustainability, and Active Learning, while also being Research-Informed.

Recent work across STEM and healthcare education (Barradell & Bell, 2021) illustrates how partnership drives institutional change.

| Ulster Principle/Quality | In Practice |

|---|---|

| Inclusivity | Ensuring diverse voices are recognised and embedded (Baxter, 2018) |

| Authenticity | Acting visibly on feedback and co-created decisions (Healey & Healey, 2019) |

| Relationships | Building trust, collaboration, and shared ownership (Healey et al., 2014) |

| Research-Informed | Applying evidence to develop meaningful practice (Ansley & Hall, 2019) |

| Digital and Data | Leveraging tools like Explorance Blue for scale and transparency |

| Wellbeing | Supporting connection, belonging, and purpose |

| Valuing Voices and Advocacy | Students influence institutional priorities through Staff-Student Consultation Committees and The Student Panel |

| Sustainability | Making partnership a long-term part of how we work (Peart et al., 2023) |

Ulster’s Commitment to Partnership

We are committed to:

- Expanding inclusive opportunities for partnership across all programmes

- Supporting staff to adopt a partnership mindset

- Celebrating and recognising student contributions, including via the EDGE Award

- Using student feedback to drive meaningful and visible change

“Student–staff partnership is not a project or product — it is a mindset, a culture, and a commitment to shared responsibility.”

(Peart, Rumbold & Fukar, 2023)

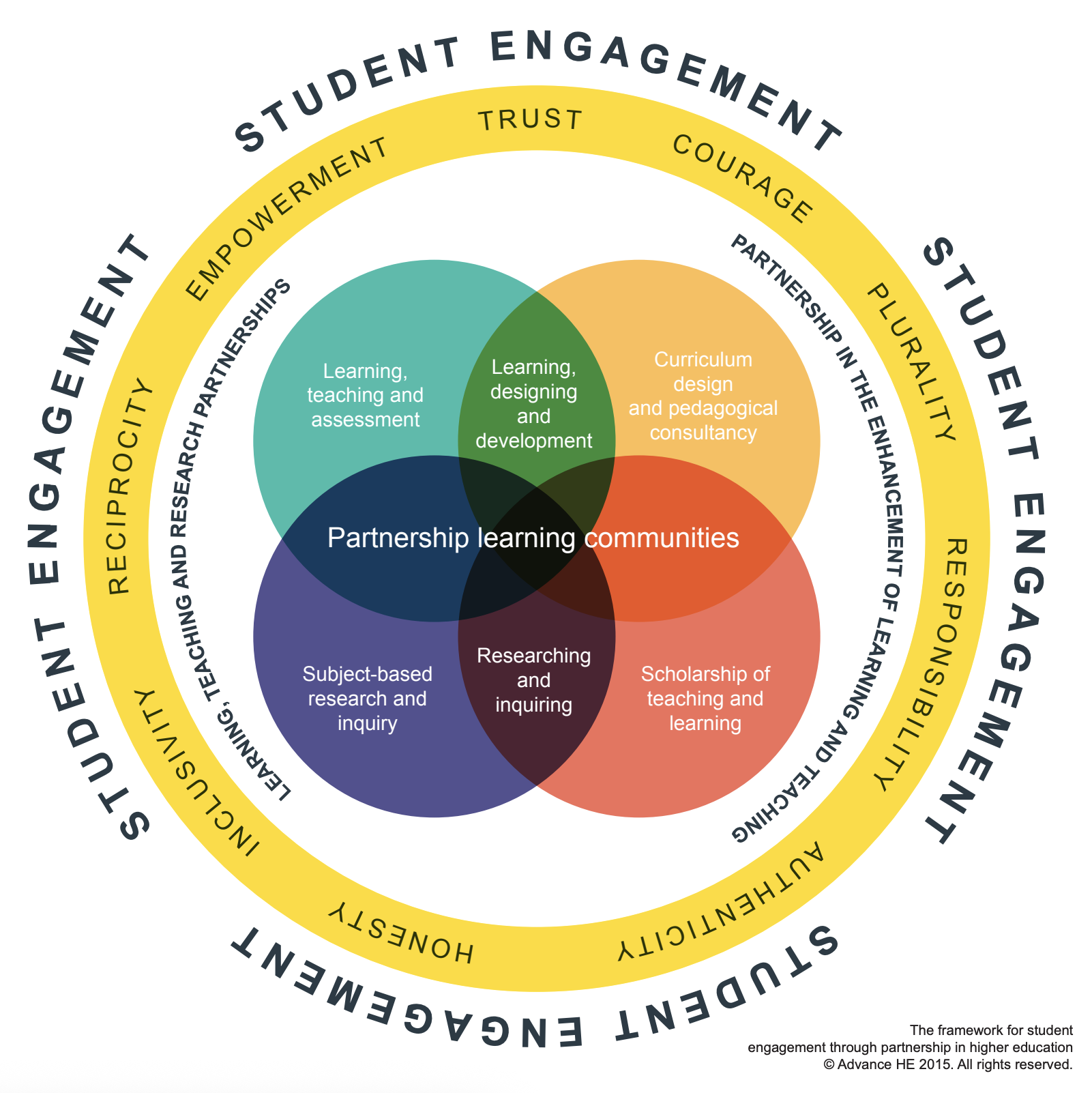

Framework for Student Engagement through Partnership

Ulster’s approach is also aligned with the Advance HE (2019) Framework for Student Engagement through Partnership.

This model identifies four interconnected values: authenticity, inclusivity, reciprocity, and shared responsibility.

These values provide a strong foundation for partnership-based approaches to learning, teaching, and enhancement across the institution.

The framework is illustrated below:

Useful Advance HE resources

- Essential frameworks for enhancing student success - Student engagement through partnership

- Student engagement through partnership in higher education

References

- Andrews, M, Brown, R and Mesher, L (2018) ‘Engaging students with assessment and feedback: Improving assessment for learning with students as partners’, Practitioner Research in Higher Education

- Ansley, L and Hall, R (2019) ‘Freedom to achieve: Addressing the attainment gap through student and staff co-creation’, Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching

- Aumiller, R L (2021) ‘Decentering power: Students as partners in dance education’, Teaching Artist Journal

- Barradell, S and Bell, A (2021) ‘Is health professional education making the most of the idea of ‘students as partners’? Insights from a qualitative research synthesis’, Advances in Health Sciences Education

- Baxter, A (2018) ‘Engaging underrepresented international students as partners: Agency and constraints among Rwandan students in the United States’, Journal of Studies in International Education

- Bovill, C (2017) ‘A framework to explore roles within student-staff partnerships in higher education: Which students are partners, when, and in what ways?’, International Journal for Students as Partners

- Healey, M, Flint, A and Harrington, K (2014) Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. York: Higher Education Academy

- Healey, M and Healey, R L (2019) Student engagement through partnership: A guide and update to the Advance HE framework. York: Advance HE

- Peart, D., Rumbold, P. & Fukar, S. (2023). Student Engagement Through Partnership: A Literature Review. Advance HE